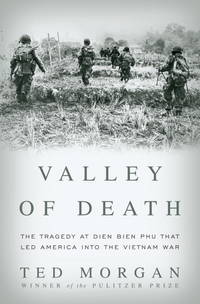

Valley of Death: The Tragedy at Dien Bien Phu That Led America into the Vietnam War

by Morgan, Ted

- Used

- as new

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- As New/As New

- ISBN 10

- 1400066646

- ISBN 13

- 9781400066643

- Seller

-

London, London, United Kingdom

Payment Methods Accepted

About This Item

Synopsis

Pulitzer Prize--winning author Ted Morgan has now written a rich and definitive account of the fateful battle that ended French rule in Indochina--and led inexorably to America's Vietnam War. Dien Bien Phu was a remote valley on the border of Laos along a simple rural trade route. But it would also be where a great European power fell to an underestimated insurgent army and lost control of a crucial colony. Valley of Death is the untold story of the 1954 battle that, in six weeks, changed the course of history.A veteran of the French Army, Ted Morgan has made use of exclusive firsthand reports to create the most complete and dramatic telling of the conflict ever written. Here is the history of the Vietminh liberation movement's rebellion against French occupation after World War II and its growth as an adversary, eventually backed by Communist China. Here too is the ill-fated French plan to build a base in Dien Bien Phu and draw the Vietminh into a debilitating defeat--which instead led to the Europeans being encircled in the surrounding hills, besieged by heavy artillery, overrun, and defeated. Making expert use of recently unearthed or released information, Morgan reveals the inner workings of the American effort to aid France, with Eisenhower secretly disdainful of the French effort and prophetically worried that "no military victory was possible in that type of theater." Morgan paints indelible portraits of all the major players, from Henri Navarre, head of the French Union forces, a rigid professional unprepared for an enemy fortified by rice carried on bicycles, to his commander, General Christian de Castries, a privileged, miscast cavalry officer, and General Vo Nguyen Giap, a master of guerrilla warfare working out of a one-room hut on the side of a hill. Most devastatingly, Morgan sets the stage for the Vietnam quagmire that was to come. Superbly researched and powerfully written, Valley of Death is the crowning achievement of an author whose work has always been as compulsively readable as it is important.From the Hardcover edition.

Reviews

The book is the definitive explanation of how the United States became involved in Vietnam. If life has a purpose, the purpose of Ted Morgan's life is to have written this book.Morgan is a French-American Pulitzer prize winning writer who served in the French army in Algeria from 1955 - 1957. By documenting in detail, based on archival evidence, the American support for the French in Indochina, and then why Eisenhower resisted sending troops during the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, he defines the obstacles that had to be overcome in order to send in the troops.A comprehensive, heart wrenching, story of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, this book is essential to anyone trying to understand the Vietnam War.

(Log in or Create an Account first!)

Details

- Bookseller

- Judd Books

(GB)

- Bookseller's Inventory #

- d26697

- Title

- Valley of Death: The Tragedy at Dien Bien Phu That Led America into the Vietnam War

- Author

- Morgan, Ted

- Format/Binding

- Hardcover

- Book Condition

- New As New

- Jacket Condition

- As New

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Edition

- 1st Edition

- ISBN 10

- 1400066646

- ISBN 13

- 9781400066643

- Publisher

- Random House

- Place of Publication

- New York

- Date Published

- 2010

- Pages

- 752

- Size

- 8vo - over 7¾ - 9¾

Terms of Sale

Judd Books

About the Seller

Judd Books

About Judd Books

Glossary

Some terminology that may be used in this description includes:

- New

- A new book is a book previously not circulated to a buyer. Although a new book is typically free of any faults or defects, "new"...