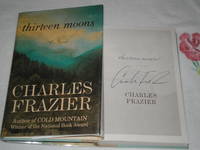

Thirteen Moons: SIGNED

by Frazier, Charles

- Used

- Fine

- Hardcover

- Signed

- first

- Condition

- Fine/Fine

- ISBN 10

- 0375509321

- ISBN 13

- 9780375509322

- Seller

-

CARSON CITY, Nevada, United States

Payment Methods Accepted

About This Item

Synopsis

This magnificent novel by one of America's finest writers is the epic of one man's remarkable journey, set in nineteenth-century America against the background of a vanishing people and a rich way of life.At the age of twelve, under the Wind moon, Will is given a horse, a key, and a map, and sent alone into the Indian Nation to run a trading post as a bound boy. It is during this time that he grows into a man, learning, as he does, of the raw power it takes to create a life, to find a home. In a card game with a white Indian named Featherstone, Will wins -- for a brief moment -- a mysterious girl named Claire, and his passion and desire for her spans this novel. As Will's destiny intertwines with the fate of the Cherokee Indians -- including a Cherokee Chief named Bear -- he learns how to fight and survive in the face of both nature and men, and eventually, under the Corn Tassel Moon, Will begins the fight against Washington City to preserve the Cherokee's homeland and culture. And he will come to know the truth behind his belief that "only desire trumps time." Brilliantly imagined, written with great power and beauty by a master of American fiction, Thirteen Moons is a stunning novel about a man's passion for a woman, and how loss, longing and love can shape a man's destiny over the many moons of a life.From the Hardcover edition.

Reviews

(Log in or Create an Account first!)

Details

- Bookseller

- skylarkerbooks

(US)

- Bookseller's Inventory #

- 017525

- Title

- Thirteen Moons: SIGNED

- Author

- Frazier, Charles

- Format/Binding

- Hardcover

- Book Condition

- Used - Fine

- Jacket Condition

- Fine

- Edition

- 1st Edition

- ISBN 10

- 0375509321

- ISBN 13

- 9780375509322

- Publisher

- Random House

- Place of Publication

- New York

- Date Published

- 2006

- Keywords

- INDIANS OF NORTH AMERICA_FICTION SOUTHERN

- Bookseller catalogs

- General; Historical;

Terms of Sale

skylarkerbooks

About the Seller

skylarkerbooks

About skylarkerbooks

Glossary

Some terminology that may be used in this description includes:

- First Edition

- In book collecting, the first edition is the earliest published form of a book. A book may have more than one first edition in...

- Brodart

- Generally used to refer to a clear plastic cover that is sometimes added to the dustjacket or outside covering of a book. The...

- Price Clipped

- When a book is described as price-clipped, it indicates that the portion of the dust jacket flap that has the publisher's...

- Number Line

- A series of numbers appearing on the copyright page of a book, where the lowest number generally indicates the printing of that...

- Fine

- A book in fine condition exhibits no flaws. A fine condition book closely approaches As New condition, but may lack the...

- Edges

- The collective of the top, fore and bottom edges of the text block of the book, being that part of the edges of the pages of a...

- Jacket

- Sometimes used as another term for dust jacket, a protective and often decorative wrapper, usually made of paper which wraps...

- Title Page

- A page at the front of a book which may contain the title of the book, any subtitles, the authors, contributors, editors, the...