From the publisher

Lloyd Jones was born in New Zealand in 1955. His best-known works include Mister Pip, winner of the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, The Book of Fame, winner of numerous literary awards, Biografi, Choo Woo, Here at the End of the World We Learn to Dance, Paint Your Wife and the short-story collection The Man in the Shed. He lives in Wellington.

Details

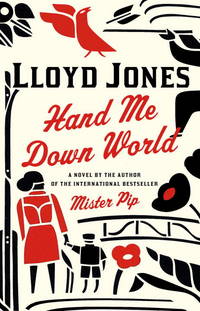

- Title Hand Me Down World

- Author Lloyd Jones

- Binding Hardback

- Edition First Edition; F

- Pages 320

- Language EN

- Publisher Knopf Canada, Toronto

- Date 2010-11-02

- ISBN 9780307400147

Excerpt

One

The supervisor

I was with her at the first hotel on the Arabian Sea. That was for two years. Then at the hotel in Tunisia for three years. At the first hotel we slept in the same room. I knew her name, but that is all. I did not know when her birthday was. I did not know how old she was. I did not know where she came from in Africa. When we spoke of home we spoke of somewhere in the past. We might be from different countries but the world we came into contained the same clutter and dazzling light. All the same traps were set for us. Later I found God, but that is a story for another day.

If I tell you of my beginning you will know hers. I can actually remember the moment I was born. When I say this to people they look away or they smile privately. I know they are inclined not to believe. So I don’t say this often or loudly. But I will tell you now so that perhaps you will understand her better. I can tell you this. The air was cool to start with, but soon all that disappeared. The air broke up and darted away. Black faces with red eye strain dropped from a great height. My first taste of the world was a finger of another stuck inside my mouth. The first feeling is of my lips being stretched. I am being made right for the world, you see. My first sense of other is when I am picked up and examined like a roll of cloth for rips and spots. Then as time passes I am able to look back at this world I have been born into. It appears I have been born beneath a mountain of rubbish. I am forever climbing through and over that clutter, first to get to school, and later to the beauty contest at the depot, careful not to get filth on me. I win that contest and then the district and the regional. That last contest won me a place in the Four Seasons Hotel staff training program on the Arabian Sea. That is where I met her.

There, instead of refuse, I discover an air-conditioned lobby. There are palms. These trees are different from the ones I am used to. These palms I am talking about. They look less like trees than things placed in order to please the eye. Even the sea with all its blue ease appears to lack a reason to exist other than to be pleasing to the eye. It is fun to play in. That much is clear from the European guests and those blacks who can afford it.

We shared a room. We slept a few feet away from one another. She became like a sister to me, but I cannot tell you her middle name or her last name, or the name of the place she was born. Her father’s name was Justice. Her mother’s name was Mary. I cannot tell you anything else about where she came from. At the Four Seasons it did not matter. To show you were from somewhere was no good. You have to leave your past in order to become hotel staff. To be good staff you had to be like the palms and the sea, pleasing to the eye. We must not take up space but be there whenever a guest needed us. At the Four Seasons we learned how to scrub the bowl, how to make a rosette out of the last square of toilet paper and to tie over the seat a paper band that declared in English that the toilet was of approved hygiene standard. We learned how to turn back a bed, and how to revive a guest who had drunk too much or nearly drowned. We learned how to sit a guest upright and thump his back with the might of Jesus when a crisp or a peanut had gone down the wrong way.

What else? I can tell you about the new appetite that came over her like a disease of the mind. She forgot she was staff. Yes. Sometimes I thought she was under a spell. There she was, staff, and in her uniform, standing in the area reserved for guests, beneath the palms, taking up the precious shade, watching a tall white man enter the sea. She watches the sea rise all the way up his body until he disappears. The tear in the ocean smooths over. She waits. And she waits some more. She wonders if she should call the bell captain. All this time she is holding her own breath. She didn’t know that until the missing person emerges—and in a different place. He burst up through another tear in the world and all of his own making. This is the moment, she told me so, she decided she would like to learn to swim. Yes. This is the first time that idea comes to her.

After eighteen months—I am aware I said two years. That is wrong. I remember now. It was after eighteen months we were moved to a larger hotel. This was in Tunisia. The tear in the world has just grown bigger. This hotel is also on the sea. For the first time in our lives it was possible to look in the direction of Europe. Not that there was anything to see. That didn’t matter. No. You can still find your way to a place you cannot see.

For the first time we had money. A salary, plus tips. More money than either of us had ever earned. On our day off we would walk to the market. Once she bought a red-and-green parrot. It had belonged to an Italian engineer found dead in the rubbish alley behind the prostitutes’ bar. The engineer had taught the parrot to say over and over Benvenuto in Italia. Thanks to a parrot that is all the Italian I know. Benvenuto in Italia. Benvenuto in Italia. We had our own rooms now but I could hear that parrot through the wall. Benvenuto in Italia. All through the night. It was impossible to sleep. Another girl told her to throw a wrap over the cage. She did and it worked. The parrot was silent. After a shower, after dressing, after brushing teeth, after making her bed, then, she lifts the wrap, the parrot opens one eye, then the other, then its beak—Benvenuto in Italia.

On our next day off I went with her to the market. We took it in turns to carry the parrot back to where she had bought it. The man pretends he’s never seen the parrot and carries on placing his merchandise over a wooden bench. She tried to give the parrot to a small boy. His eyes grew big. I thought his head would explode. He ran off. The parrot looked up through the bars, silent for once, looking so pitiful I was worried she was about to forgive it. But no. In a tea house the owner flirted with her but when she tried to gift the parrot he backed off with his hands in the air. In the street a man stopped to poke his finger through the bars. He and the parrot were getting on. But it was the same thing. They were happy to look, to admire, but no one wanted sole charge of that parrot. She began to think she would be stuck with that parrot forever.

I took the cage off her and we boarded a bus. The passengers were waiting for the driver to return with his cigarettes. I walked down the aisle dangling the cage over the heads of the passengers. Some fell against the window and folded their arms and closed their eyes. One after another they shook their heads. Back in the market people talked to the parrot, they stuck a finger through the bars for the parrot to nibble, they cooed back at the parrot. It turned its head on its side and gave them an odd look which made everyone laugh. But no one wanted to own a parrot. She asked me if I thought there was something wrong with her. Because how was it that she was the only one who had thought to own a parrot?

We returned to the hotel. It wasn’t quite dark. We could hear some splashing from the pool. Some children. People were sitting around the outside bars. She took the parrot from me and set off to the unvisited end of the beach. I followed because I had come this far, and the whole time I had been following, so that now, just then, I did not know what else to do with myself. Down on the sand she kicked off her sandals. She placed the cage down and dragged one of the skiffs to the water. Had she asked for my advice I would have told her not to do this thing. Now I regret not saying anything. I was tired. I was sick of sharing the problem. I wanted only for the task to be over with. As she pushed the skiff out the parrot rolled its eye up at her, to look as though it possibly understood her decision and had decided it would choose dignity over fear.

In the night the wind blew up. I stayed in bed. But I can say what happened next because she told me. She also woke to the waves slapping on the beach but dozed off again without a thought for the parrot. The second time she woke it was still early. No one was up when she walked across the hotel grounds. She found the skiff hauled up on the beach. The cage was gone. Further up the beach she found the damp corpse of the parrot on top of the smouldering palm leaves. The groundsman was raking the sand. When she asked him about the cage he looked away. She thought she was going to hear a lie. Instead he told her to follow him. They go to the shed. He pulls back the beaded curtain. On the bench she sees the thin bars of the cage. The cage itself no longer exists. The bars have been cut off. She picks up one—holds it by its wooden handle, presses the sharpened point into the soft fleshy part of her hand. Well, she took the sticking knife as payment for the cage. That’s the story about the knife.

She told me once that as soon as you know you are smart you just keep getting smarter. For me it hasn’t happened yet. That’s not to say it won’t. When the Bible speaks of eternity I see one long line of surprises. It’s not to say that that particular surprise won’t come my way. I’m just saying I’m still waiting. But she got there first when she was promoted to staff supervisor. Now it was her turn to tell the new recruits that they smelt as fresh as daisies. You should see her now. The way she moved through the hotel. She would change the fruit bowl in reception without waiting to be asked. She says ‘Have a nice day’, as she has been taught, at the rear of the heavy white people waddling across the lobby for the pool. When a guest thanks her for picking up a towel from the floor she will smile and say ‘You’re welcome’, and when told she sounds just like an American she will smile out of respect. The tourists replace one another. The world must be made of tourists. How is it I wasn’t born a tourist? After four years in the hotel I could become a tourist because I know what to take pleasure in and what to complain about.

White people never look so white as when they wade into the sea under a midday sun. The women wade then sit down as they would getting into a bath. The men plunge and then they swim angrily. The women are picking up their towels from the sand as their men are still bashing their way out to sea. Then the men stop as if wherever they were hoping to get to has unexpectedly arrived. So they stop and they lie there with their faces turned up to the sky. When a wave passes under them they rise like food scraps, then the wave puts them down again. I used to wonder if these waves were employed by the hotel. I wondered if they too along with the palms had been through a hotel training course. ‘Look how gently the sea puts them down,’ she said. Look—and I did. ‘See,’ she said. ‘There is nothing to be afraid of.’

One of the floating men was called Jermayne. He happened to catch her watching the white people at play in the sea. Not this time, but another time. I wasn’t there. But this is what she told me. I hadn’t set eyes on him yet so this is what she said about Jermayne. He was a black man. Yes, he had the same skin as her and me but he hadn’t grown up in that skin. That much was easy to see. He had a way about him.

I remember asking her once—this would have been back at the other hotel on the Arabian Sea. We’d been lying there on our beds making lists of things to wish for, and I said, ‘What about love?’ Everyone needs loving. That too is in the Bible if you know where to look. I said, ‘Don’t you want to lie down with a man?’ She burst out laughing. Now, under the palms in the hotel ground, I asked her the question again. This time she looked away from me. She focused—as if there were so many ways of answering that question she couldn’t decide on just one.

But with this man I can see she is interested. When I see her with him I stop whatever I’m doing to watch. She starts playing with her hair. Now she produces a smile I have never seen before. When I reported back to her what I had seen she said I had been blinded by wishfulness on her behalf. She said Jermayne had offered to teach her to swim. ‘Well, that’s good,’ I said. ‘That way you are bound to drown.’ See how negative I sound. I don’t know why that is. Why did I decide I didn’t like Jermayne? Maybe instead of being smart I have developed some other kind of knowing.

Maybe it was his confidence. Maybe it was his unlived-in blackness. Maybe I just didn’t like him. Does there have to be a reason? Then—I will say this here, just place it down for the time being. I thought I saw him. No. What do I mean by ‘thought’? I did. I saw him with a woman. They were crossing the lobby in a hurry. But after that I didn’t see her again. I decided she must have been another guest, entering the lift when he did, because the next day it was just Jermayne in the breakfast room.

When I saw them together, my friend and him, there were two Jermaynes. One is with her—that one she can see. But at the same time there is another Jermayne. This one is standing close by looking on and smiling to himself like he knows her thoughts before she does. He saw her reluctance to get in the pool whenever guests were using it. He read her like an open book. He had to insist—she laughed him off, pretending she didn’t want to get wet after all. It was the same at the pool bar. Before Jermayne she had never had a drink with a hotel guest. Never ever—no, no, no, and the barman knew it, the stars knew it, the night knew it, the palms stood stunned in the background, and the little droplets splattering the poolside reminded everyone of the silence and the rules. She said Jermayne made it feel all right. Then it began to feel more and more right. She was no drinker. He had to explain what an outrigger was—the boat and the drink, and after that cocktail she said her thoughts drifted off to the parrot and its night out on the skiff and didn’t drift back until Jermayne started to talk about his upbringing. An American father, a German mother. He grew up in Hamburg but now lived in Berlin. He had his own business, something with computers.

She is getting down off her stool when he reaches for her hand, then he leans over her and kisses her lightly behind the ear. A group of tourists were laughing like jackals at one end of the bar. She looked to see if anyone had seen. No one had—but Jermayne had, he had seen her looking, seen her eyes looking for trouble, for blame. He smiled. He told her to relax. She was safe. He wouldn’t hurt her or do anything that would get her into trouble. That’s not my calling—that’s what he told her. He said now listen—and she did.

The next day—it was after her shift—I saw them paddle a skiff out to the artificial reef. I saw them pull the skiff up the beach and walk to the ocean side. This was her first swimming lesson. I didn’t see any of it. This is just what she told me, and this was a good deal later, months later following the events that I am leading up to.

Her first swimming lesson begins with Jermayne walking into the sea up to his waist. He looks around to see if she has followed. She hasn’t moved from the sand. He tells her there’s nothing to be afraid of. If he sees a shark he will grab the thing by its tail and hold it still until she has run back to shore. She is afraid, but she enters the water. The whole time she doesn’t take her eyes off him. To do so, she feels, will see her tumble into an abyss. So, there they are walking deeper into the sea. She is also walking deeper into his trust—that is also true. The rest is straightforward. She did what he asked her to do. She lay down on the sea. She turned herself into a floating palm leaf. She felt his broad hand reach under her belly. Then she begins to float by herself. Every now and then her belly touches Jermayne’s ready hand. Then, she said, it was just the idea of his hand that kept her afloat. I have never put my head under the sea so I can only go on what she said about it pouring into her ears and up her nostrils. I thought, I will never do that. I will never ever allow the sea to invade me. But she’d done it all wrong. That’s the point—what she wished me to know. She’d forgotten to take a breath.

Jermayne gave her buoyancy. He taught her how to float like a food scrap. But it was a Dutchman who properly taught her. He never used the words ‘trust me’. If he had she would not have listened. He would say ‘like so…’ and demonstrate the frog kick and the crawl. I haven’t learnt those strokes myself, just the words. Frog kick. I like that. I’m not sure about the word ‘crawl’ any more, especially when I look out at a sea that is as vast as any desert. She tried to show me these things by lying flat on a bed. That’s where she used to practise her strokes when the guests were using the pool. I had to pretend the bed was the sea. But I did not want to swim. Besides, what I have just said belongs to another story.

What I meant to say is this. With Jermayne it was all about her trusting him. And she did. Some of the things I will say now are what she told me. I was not there. How could I be? But this is what she said. When he asked her if she ever felt lonely, she had to stop and think. It had never occurred to her that she might feel lonely. I often wonder about that magic. Where does that feeling come from? If we don’t know the word for our wants maybe that is better. Anyway, they are out at the pool bar. Everyone has moved inside. They are by themselves. Perhaps the barman is there. I don’t know. After asking if she is ever lonely he touches her hand, moves his hand to her arm, now her neck. He asks if he can come to her room. ‘No,’ she tells him. She is the supervisor. She would have to sack herself. ‘In that case,’ he says, ‘come to my room. Come and lie with me.’ She looks around in case someone overheard. ‘Trust me,’ he says.

In Jermayne’s room there was just the one embarrassing moment—there may have been others which I have since forgotten, but this is the one that has stuck. At some point he asks her if she would like to use the bathroom. She’s surprised that he should ask. Why would he? Does he know when she needs to pee? Then she realises why he asked. It’s because she has stood there rooted to the spot staring in at the white lavatory. It was the marvel of being in a guest’s room without rushing to clean the toilet bowl and tie a paper band around it to declare it is hygienically fit for use. Or to spray the door knobs so the room will smell nice or to punch the pillows and turn up the bed.

She stayed the night—well not quite because she woke to the noise of the generators. There had been a power cut. She got out of bed and dressed and returned unseen to the staff quarters. I know she stayed with him the next night, and the one after. Then Jermayne flew back to Germany. He said he would ring. I did not think he would. But I underestimated him. Sometimes I would see her on the phone in the lobby and I would know it was him calling across the sea. A month later he was back, this time for a shorter stay, and it must have been during this period that she became pregnant. I was the only one to know. At first I should say, because eventually there is no hiding a pregnancy.

Jermayne came and stayed another two times. The last time was for the birth. The hotel gave her time off. Jermayne rented an apartment in a nice neighbourhood on the other side of town from the market. I visited her there once. It was nice, quiet. There were no flies. He insisted she stay there with him. For a short time they lived as man and wife. She rang me once at the hotel. She said she just wanted to hear my voice, to be sure we still occupied the same world. She was visited by a doctor. She had never seen a doctor. He took her blood pressure and her pulse and put his hands where a midwife would. Jermayne was there, holding her hand. She listened to him ask the doctor questions. Many, many questions. Until he was satisfied the baby would be a healthy one. She had never known anyone to show so much care. When her waters broke there was a taxi waiting to take her to hospital. That Jermayne thought of everything.

They hadn’t talked about what would happen next. I was sure Jermayne would take her to Germany. There she might start a new life. She was willing. I sensed that. She hoped that was what Jermayne had in mind. She never did ask. She did not want to burden him with a surprise. Of course she hoped it would not be a surprise, that the plans she saw clicking away behind his eyes involved her. He was with her at all times, even for the delivery, and before, too, breathing with her, holding her hand.

Many hours later a baby boy is clamped to her breast. And there is Jermayne with a bunch of flowers. There are forms to fill out. Jermayne has thought of everything. Some of the forms are in another language, Deutsch, she sees. She checked with Jermayne. He explains, it is like taking possession of something. You have to sign for it. Like signing in for a room. So she did, she signed where he indicated on the forms. After two days in hospital a taxi brought her back to Jermayne’s apartment. He’d been out to buy baby clothes. He put her and the baby to bed. At night they lay with the baby between them. Once she asked Jermayne to come and lie next to her. She wanted to feel his hand on her, like the times when he was teaching her how to float. He turned his head on the pillow. A car’s headlights found the window and in that single moment she saw him with his eyelids closed.

He insists she stay in bed. She has to mend. She tells him nothing is broken. But he doesn’t hear. Jermayne has to do things the Jermayne way. He doesn’t hear what he doesn’t want to hear.

One morning she woke to the sound of the shower running. It was very early, yet when Jermayne comes out of the bathroom he is fully dressed. His face alters a little to find her sitting up in bed. He puts on a smile. Yes. A nice smile. A smile to calm the world. He puts a finger to his lips to shush her. They don’t want to wake the baby. He sits on the edge of the bed. He bends down to tie his shoelaces. She watches him doing this, wanting to speak, to ask what he thinks he’s lost because now he’s walking from one corner of the apartment to another. Now he’s found it. A baby carrier. It’s the first time she’s seen it. Now he comes to his side of the bed and picks up the baby. He presses his nose to its belly. He always does that. She likes it when he does that. Jermayne will be a good father, a loving father.

The baby stirs; its eyes are still fiercely shut when it opens its mouth and makes a waking noise. At last they can talk. He says it is time for the baby to get some air. He doesn’t want to take him out when the sun is up. It will be too hot. He stresses to her the importance that he get used to different air. So he will take the baby for a short walk. Not far. He doesn’t want to tire him out. Just as far as the gardens at the end of the road and back. He holds the baby out to her. ‘Kiss Mummy goodbye,’ he says. She kisses the baby’s cheek. Then she lies back, head on pillow, hands on her belly, eyes closed. Then she reaches a hand into the space beside her. How strange it is to find that space empty. How quiet the apartment suddenly feels. It feels wrong. She tries keeping her eyes closed but it is no good. There is nothing to mend, no tiredness to collapse into. That’s when she gets out of bed. She walks to the window. Maybe she will see Jermayne and the baby, and she does. There they are—well, the top of Jermayne’s head. There is also a taxi. The back door opens and a woman gets out. Jermayne hands over the baby and the woman cradles the baby in her arms, rocks the baby, looks at its face for a long time, then she lowers her face into the bundle. Jermayne holds the door of the taxi. He looks up once to the windows of the apartment. Now the woman and the baby get in the back, followed by Jermayne, the door closes, and the taxi moves up the street.

The rest I don’t know. I don’t know how she spent the hours waiting for Jermayne to return. I don’t know what her thoughts were. But, for only the second time in my life, there is a phone call for me. I hear the whole story, and when she comes to the bit about the strange woman waiting by the taxi I know who that woman is; it is the same woman I thought I saw with Jermayne months earlier. They crossed the lobby together. She went into the lift ahead of him. At that moment I felt quite sure they were together. In a hotel you quickly learn who is alone and which ones are couples, and which ones are unhappy. And when you change their sheets you know more still. I never saw that woman again. And remember, at breakfast there was just Jermayne.

But as soon as I hear about the woman getting out of the taxi I see the woman walking slightly ahead for the lifts, and I see Jermayne gesture with his hand for her to go in first, and I see, as if for the first time, the woman open and close her purse, and as the lift doors are closing I see her turn to Jermayne. This is information that sits inside my mouth. Perhaps one day I will spit it out and tell her. But as she is telling me about that woman getting out of the taxi I hold my tongue and at the same time I feel a prickly heat cover me from head to toe. This is my cross to bear. But listen to what I say to myself. If I tell her, I feel I will lose a friend. Because if I tell her she will think she has lost a friend. A friend would have shared such information. Why did I not say something at the time? She will want to know. And I don’t know what I might say. Now I do know. I would have said I wanted her to be happy.

It was another two days until my day off. I walked across the city to the apartment. It was very hot. No one else was out. There were cars. But no one was walking. I was walking because I had only enough money for the trip back to the hotel in the taxi.

I was expecting her to be upset. I’m not saying she wasn’t. But most people when they are upset will cry or wave their arms about. Not her. She was still, very still. Still as a hotel palm on one of those hot breathless days. I gave her a hug but I can’t say I felt flesh, not breathing, living kind of flesh. She lowered her eyes away from me. She would not let me see her or get near to how she felt. Perhaps there was no way of getting closer. I only know she was glad I was there to bring her home to the hotel.

The hotel managers were surprised to find her back on the roster. Like everyone else they had imagined she would move away with Jermayne. They thought of her story as a good luck story. A bit of star dust had fallen out of the sky and landed at her feet. That’s how they saw it. I backed up her miscarriage story. The management were kind. They gave her time off. One of the women gave her a hug. A man we hardly ever saw, he had something to do with laundry, he gave her flowers. Soon she was back in uniform, back to supervisor, but there was no going back to that person she had been.

She did not smile at the guests. She looked right through them when they made their little complaints. She did not care. I saw her take a skiff out to the artificial reef. She did that by herself. I would like to have gone out there but she didn’t invite me and I didn’t ask because these were pilgrimages. I could see her quite clearly, walking up and down that shoreline looking off in the direction of Europe.

One afternoon while I am looking at that solitary figure on the reef Mr Newton from management comes up behind me and whispers in my ear. How would I like to be made supervisor? Well I am still that person today. I don’t know what tomorrow will bring. I am happy. I believe in love. I would like some of that to fall out of the sky and land at my feet one day. But before I bend down and pick it up I will be sure of what it is first.

Media reviews

“Haunting. . . . A delicate exploration of how our words voyage away from our thoughts, and how we seek asylum from actual experience in the crafted realm of memory.”

—The Telegraph

“A . . . nomadic spirit informs his creative imagination. . . . Daring and emotionally involving.”

—The Independent

“Unselfconsciously cosmopolitan both in its story and in its register, and Jones is the kind of writer who can slip naturally from the low to the lyrical in the space of a paragraph.”

—The Observer

“A seamless narrative as compelling as that of any thriller. . . . [Jones is] one of the most significant novelists writing today.”

—The Sunday Times

“A beautifully constructed, genuinely affecting book with immense heart and a varied cast of expertly inhabited characters, each with his or her own distinctive voice and milieu.”

—Australian Book Review

About the author

Lloyd Jones was born in New Zealand in 1955. His best-known works include Mister Pip, winner of the Commonwealth Writers' Prize and shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, The Book of Fame, winner of numerous literary awards, Biografi, Choo Woo, Here at the End of the World We Learn to Dance, Paint Your Wife and the short-story collection The Man in the Shed. He lives in Wellington.

More Copies for Sale

Hand Me Down World

by Jones, Lloyd

- Used

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- Used - Fine in Fine dust jacket

- Edition

- First Edition; First Printing

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 13

- 9780307400147

- ISBN 10

- 030740014X

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Wheatfield, New York, United States

- Item Price

-

£7.32£4.88 shipping to USA

Show Details

Hand Me Down World

by Jones, Lloyd

- Used

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- Used - Fine in Fine dust jacket

- Edition

- First Edition; First Printing

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 13

- 9780307400147

- ISBN 10

- 030740014X

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Wheatfield, New York, United States

- Item Price

-

£8.13£4.88 shipping to USA

Show Details

Hand Me Down World

by Jones, Lloyd

- Used

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- Used - Near Fine in Near Fine dust jacket

- Edition

- First Edition

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 13

- 9780307400147

- ISBN 10

- 030740014X

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Wheatfield, New York, United States

- Item Price

-

£8.13£4.88 shipping to USA

Show Details

Hand Me Down World

by Jones, Lloyd

- Used

- near fine

- Hardcover

- first

- Condition

- Used - Near Fine

- Edition

- First CDN Edition, 1st Printing

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 13

- 9780307400147

- ISBN 10

- 030740014x

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Lyndhurst, Ontario, Canada

- Item Price

-

£32.56£20.35 shipping to USA

Show Details

Hand Me down World

by Jones, Lloyd

- Used

- Hardcover

- Signed

- first

- Condition

- Used - Very Good+

- Edition

- Canadian First

- Binding

- Hardcover

- ISBN 13

- 9780307400147

- ISBN 10

- 030740014x

- Quantity Available

- 1

- Seller

-

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

- Item Price

-

£32.56FREE shipping to USA

Show Details

Remote Content Loading...

Hang on… we’re fetching the requested page.

Book Conditions Explained

Biblio’s Book Conditions

-

As NewThe book is pristine and free of any defects, in the same condition as when it was first newly published.

-

Fine (F)A book in fine condition exhibits no flaws. A fine condition book closely approaches As New condition, but may lack the crispness of an uncirculated, unopened volume.

-

Near Fine (NrFine or NF)Almost perfect, but not quite fine. Any defect outside of shelf-wear should be noted.

-

Very Good (VG)A used book that does show some small signs of wear - but no tears - on either binding or paper. Very good items should not have writing or highlighting.

-

Good (G or Gd.)The average used and worn book that has all pages or leaves present. ‘Good’ items often include writing and highlighting and may be ex-library. Any defects should be noted. The oft-repeated aphorism in the book collecting world is “good isn’t very good.”

-

FairIt is best to assume that a “fair” book is in rough shape but still readable.

-

Poor (P)A book with significant wear and faults. A poor condition book can still make a good reading copy but is generally not collectible unless the item is very scarce. Any missing pages must be specifically noted.